Family life

Child injured by scissors. Italy, Veneto, late 15th century, tempera on panel, 27.7 x 36.3 cm (including frame). Lonigo, Madonna dei Miracoli, Museo degli ex voto (Lora et al., no. 9).

Family life was profoundly shaped by religious belief. From birth to death, devotional rituals permeated the daily lives of Renaissance Italians. Religious imagery was a constant presence in many homes, appearing on ordinary household objects – dishes, combs, chests – as well as works of art. Representations of the Madonna and Child and the Holy Family reminded the laity that infancy played a special part in the Catholic faith; parents were expected to instruct their children in correct beliefs and practices before anything else. For Italian Jews domestic space was an especially important locus for ritual and religious acts, as surviving objects testify.

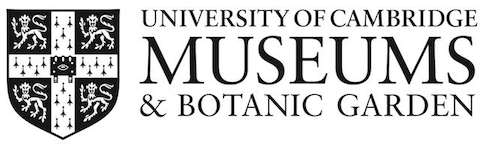

The Madonna, Christ and the Saints

Workshop of Giacomo Mancini (active 1541–54), panel with The Crucifixion. Italy, Umbria, Deruta (probably), 1556, tin-glazed earthenware (maiolica), 40 x 41.3 x 2.5 cm. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, mar.c.57-1912.

In the Renaissance, men, women and children entered into deeply personal relationships with divine figures. These were characterised by reverence and awe, but also by affection and familiarity. Strong ties bound members of a family to their household Madonna, who provided them with succour and comfort over the years. Images and texts encouraged empathetic identification with the suffering Christ. The pantheon of saints acted as intercessors, and provided targeted help for specific issues and problems. Over the course of the period these holy figures featured in a vast array of books, prints, paintings and objects, many of them destined for the domestic realm.

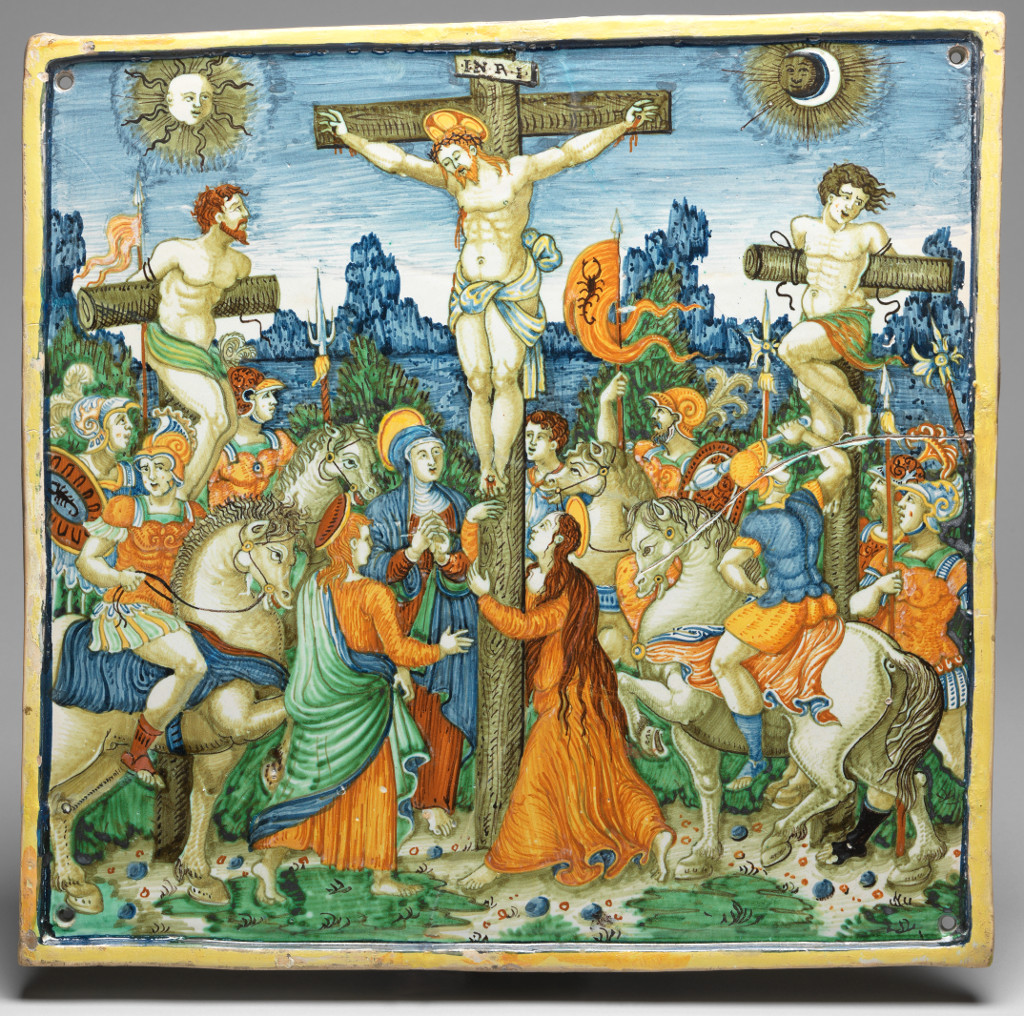

Practices of prayer

Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto). c.1497–1502, Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist, tempera on panel with oil glazes, 56.7 x 40.7 cm. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, no. 119

It was primarily through prayer that Renaissance Italians connected with the divine: they were exhorted to pray in their homes every day. Often, this involved the oral recitation of memorised words, such as the rosary. But prayer encompassed a wide range of practices – religious reading, meditating upon an image, calling for intercession, touching a relic, the possession of scraps of paper marked with holy words. Although contemporaries disagreed as to which form was most effective, almost all prayer required worshippers to make use of material objects and works of art, and a rich variety of items was made expressly for this purpose.

Pilgrimage and Miracles

Sick man in bed prays with rosary, attended by his wife and children (detail) Italy, Naples (possibly), 16th century, tempera on panel, 28.7 x 43.8 cm. Naples, Il Museo degli Ex voto del santuario di Madonna dell’Arco (Giardino and Rak, no. 329)

Renaissance Italy witnessed an explosion of interest in the miraculous. New cults sprung up devoted to Madonnas who wept or crucifixes that bled. Devotees undertook pilgrimages to these shrines, and to sites of religious significance in Italy and further afield. They brought home fragments chipped from the fabric of holy places, relics of the bodies of saints, souvenirs of the Passion, and cheap mass-produced items as records of their journeys. Many pilgrimages were made in order to give thanks for a miracle, and painted wooden boards that recorded these wondrous events were left at shrines. Rarely seen outside Italy, these ‘ex-votos’ provide fascinating glimpses into the lives of ordinary people, and record the accidents, illnesses and misfortunes from which they were delivered by divine intervention.

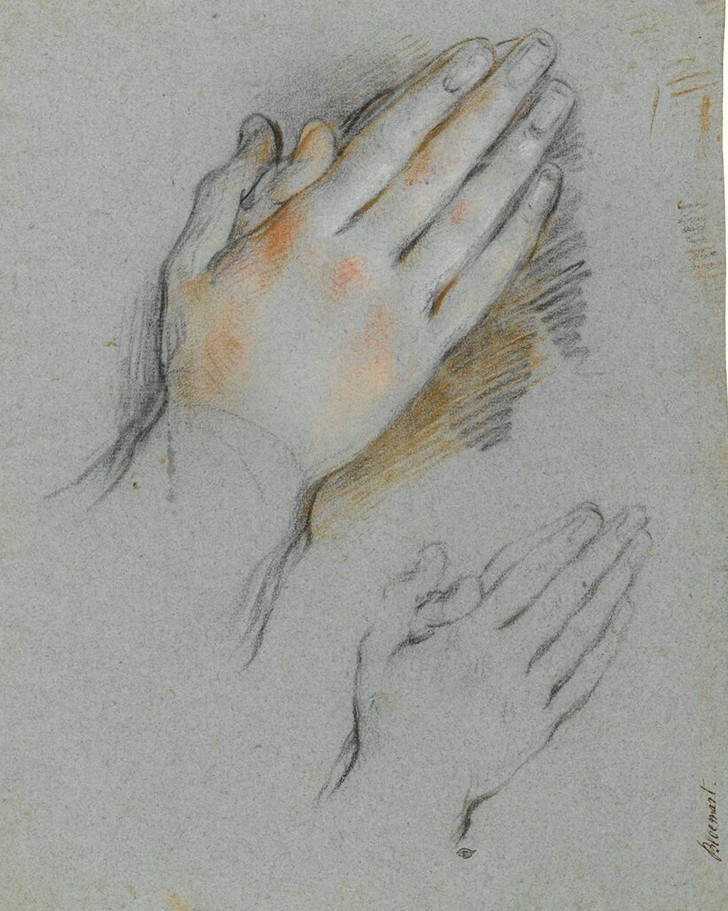

Reform and renewal

Follower of Federico Barocci (1528/35-1612), Studies of hands clasped in prayer Italy, later 16th century, black, red, white and brown chalks on blue paper, laid down, 28.4 x 23 cm. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, PD.158-1963

Ideas about proper religious practice changed over the course of the Renaissance, and were hotly debated. The seismic events of the Reformation resulted in vigorous defences of the use of images in devotion, but also renewed concern about illicit and immoral behaviour. The Church attempted (not always successfully) to regulate domestic religious life, and to combat heretical practices that were taking place behind closed doors. At the same time, it nurtured new modes of devotion that appealed to all the senses and worked on the emotions. By the close of the sixteenth century, the homes of even poor Italian families were full of the paraphernalia of piety: rosaries, cheap devotional prints, candles and crucifixes.